Foster Care and Neglect: What You Should Know

Oftentimes, youth enter foster care due to neglect. According to the Adoption and Foster Care Analysis and Reporting System (AFCARS) data for Fiscal Year 2021, of the nearly 400,000 children in foster care in the United States, 63% of these youth found themselves within the child welfare system because neglect – over 130,000 youth in total.

In comparison, 36% of youth in the child welfare system were there because of parental substance abuse. Further, 12% of children were placed into foster care because they had been physically abused by their parents or guardians.

Because so many kids and teens are placed into foster care because of neglect, it’s important to understand what is meant by the term – and how child welfare agencies are rethinking their understanding of and approach to neglect when working with children and families.

Defining Neglect in a Child Welfare Setting

It is important to note that there is no universal definition of neglect in the United States. As the Children’s Bureau has noted, “Child abuse and neglect are defined by Federal and State laws. At the State level, child abuse and neglect may be defined in both civil and criminal statutes.”

The State of California has two definitions for neglect, one for what the state determines as general neglect and severe neglect. The state defines general neglect as “the negligent failure of a parent/guardian or caretaker to provide adequate food, clothing, shelter, or supervision where no physical injury to the child has occurred.” In comparison, severe neglect “refers to those situations of neglect where the child’s health is endangered, including severe malnutrition.”

It is important to note that neglect is different from abuse, both at the federal and state level. In California, the state has specific definitions and criteria in instances when youth are emotionally abused, sexually abused, physically abused, or exploited.

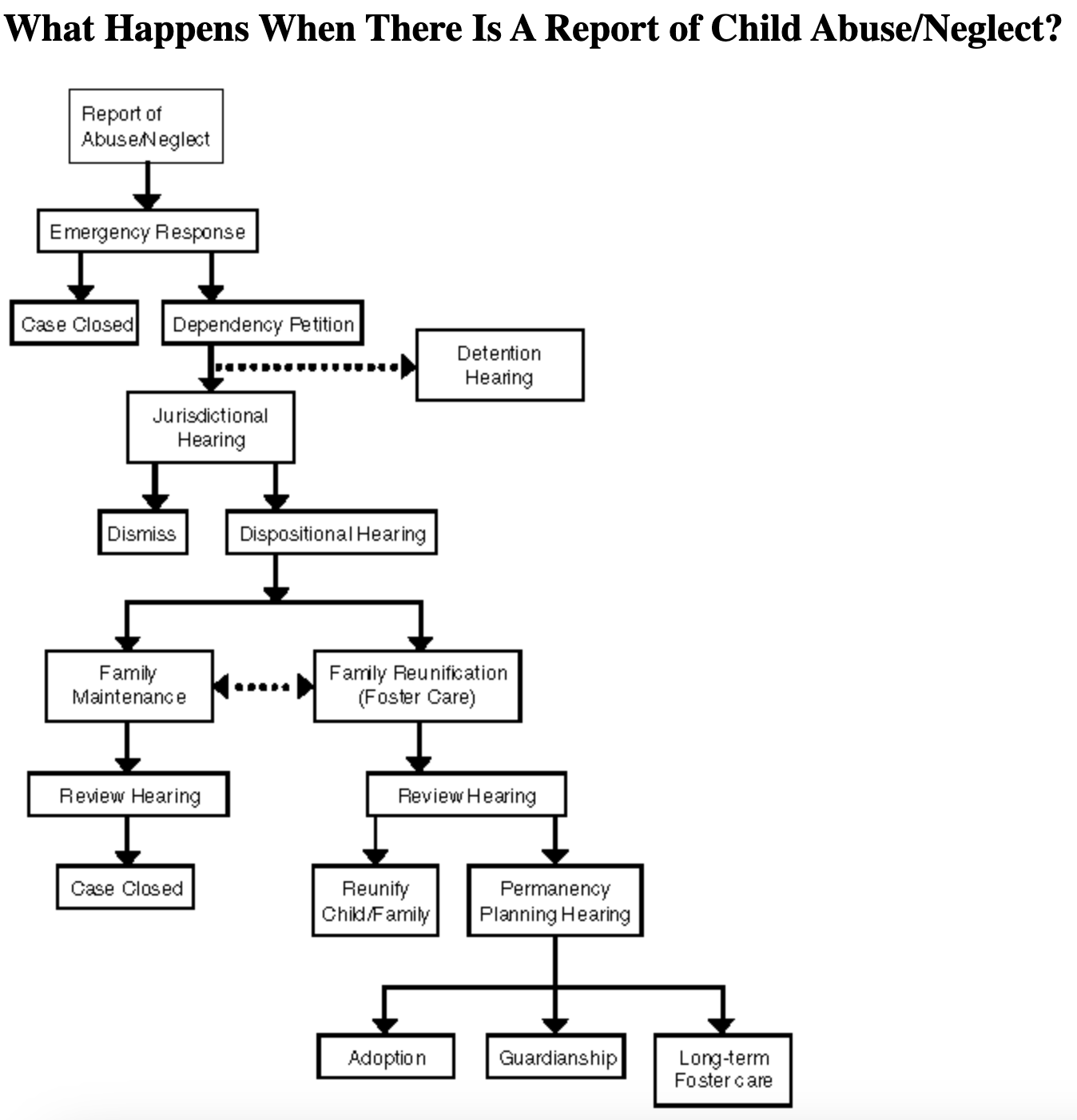

Source: State of California Legislative Analyst’s Office

Rethinking Neglect in the Child Protective and Juvenile Justice System

As the data shows, most children represented in the child welfare and foster care system find themselves in the care of foster parents due to issues of abuse or neglect. Over the years, however, some critics have charged that too often, poverty is conflated with neglect. Considering the trauma caused by placing youth in foster homes and the negative mental health problems such a removal often leads to, does it make sense to remove youth from their biological families simply due to issues related to poverty?

“Society continues to maintain a strong attachment to the assumption that both poverty and neglect reflect caregivers’ failures to accept personal responsibility. A large segment also believes that poverty and neglect both represent antisocial behavior. These beliefs, to many, justify the idea that poverty and neglect should be addressed through the authoritative intervention of government to exercise social control over both poor families and neglectful parents,” write Tom Morton, former president of the Child Welfare Institute, and Jess McDonald, former child welfare director for the state of Illinois. “We submit that this belief structure as it applies to neglect is based on an antiquated idea of child protection that was rooted in a desire to address serious physical and sexual abuse, which indeed is antisocial behavior. Because this was the focal point, the child protection system (CPS) was significantly fashioned after the criminal justice system. But the vast majority of neglect, and poverty, has nothing to do with antisocial behavior. The first response to the majority of child neglect referrals should not be an authoritative one driven by the same cultural assumptions underpinning the criminal justice system. Nor should it primarily employ core practices and policies adapted from that system. Unless probable cause exists to support a possible criminal prosecution, or circumstances clearly indicate an immediate threat of serious harm to children in the household necessitating immediate removal, referrals for neglect should first receive a public-health response.”

Indeed, even the Children’s Bureau has acknowledged that “Research tells us that families who are experiencing poverty are far more likely to be reported to child protective services (CPS) than families with more resources.” They recommend that mandated reporters consider the role of poverty, and that county, state and federal officials should seek to first provide families with support around health care, [childcare], housing support, etc., whenever possible as opposed to seeking to remove a child from their home. In some instances, these kinds of supports can alleviate any potential neglect concerns.

“Poverty is a complex, ongoing issue that has significant societal, systemic, organizational, community, and family effects. The effects of poverty can be harmful to children, but it is critical to recognize that poverty alone does not equal neglect,” the Children’s Bureau has written. “Families may experience and remain in poverty despite efforts to advance their economic situation. Thus, when families experiencing poverty come to the attention of the child welfare system, it is important to consider the families’ knowledge of and capacity to access social support and help connect them with resources. Economic and concrete support interventions are not a panacea for child neglect and do not eliminate the need for other social work strategies. However, growing evidence indicates that providing such support can reduce maltreatment rates overall, neglect rates, and the number of families coming to the attention of CPS agencies.”